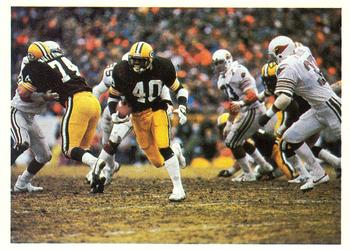

It’s almost impossible to exaggerate how much Bart Starr was adored and admired in Green Bay. Not merely a Hall-of-Fame superstar and 2-time Super Bowl MVP who led the Packers to 5 championships, Starr—a devout Christian who supported many charities—engendered a mythology of greatness and saintliness. He had championship rings—and a halo. Almost everybody in tiny Green Bay had a heartwarming Starr story: words of encouragement, acts of kindness, patience with autograph-demanding fans.

One man came to Starr’s home, where Starr was meeting with a coach, wanting an autograph for his father, who waited in the car, and, over the man’s objections, Starr left the meeting to chat with the enthralled fan.

Another said: “I met Bart in Milwaukee, and he said, ‘Next time you’re in Green Bay, drop by for a Coca-Cola.’”

(Everyone called him “Bart.”)

“My brother was driving over the river bridge, and it was 20 below, and his car broke down, and the first one to stop to help was Bart.”

And on and on.

Players and colleagues over many years uniformly used variations of one phrase to describe him: “He was a fine human being.”

After Starr’s glory seasons as a player, the Packers suffered years of embarrassing mediocrity. The city’s moniker, “Titletown,” became a mocking taunt. Despite Starr having no head coaching experience, a powerful movement grew in Green Bay for the Packers to hire Starr. Citizen-by-citizen, Packers fans collectively decided Starr, whose coaching experience was only 1 season as Packers quarterbacks coach (1972, when they won the division—a faint sign of hopefulness), could translate his championship aura and quarterbacking-on-the-field success to on-the-sidelines coaching success and restore the quaint town’s tarnished image. The slogan “Fresh Start With Bart” proliferated all over town: bumper stickers, handmade signs fluttering in Lambeau Field stands. It was everywhere.

One fan said, “He was a smart, take-charge guy. We assumed he was everything we needed in a head coach. I thought his lack of experience would be overtaken by his status.”

Another fan said, “We thought the football gods would smile on us.”

Packers historian Cliff Christl said, “That was almost a case where the fans hired the coach.”

The Packers executive committee, according to former Packers historian Lee Remmel, “felt they had no choice because there was so much groundswell of enthusiasm.” The executive committee was a small group selected from the Packers board of directors, and it ran the team, along with the president, whom they chose. They were all members of the Green Bay community and routinely interacted with these avid Bart Starr-endorsers. In line at the grocery store, one might get a nudge from behind: “You’re going to hire Bart, right?”

All of Starr’s close friends advised he decline the offer, citing his inexperience, his promising business pursuits, and the difficulty of the risky job. But, deeply loyal to the team that let him rise from lowly 17th-round pick to 5 championships, he said, “They could have cut me, and they didn’t.”

Starr was named the Packers head coach on Christmas Eve, 1974. In a photo of that announcement, on the wall behind him and his wife, both smiling broadly, were banners that featured the Packers’ many previous championships. The banners over his shoulder demanded: Put more up here.

Then-corporate general manager Bob Harlan said of the fans’ thrill at Starr’s return to the Packers, “It was almost like Jesus was reborn.”

Through early disappointing seasons, Starr remained confident that with time he would succeed. Starr was not a naturally great player but worked himself into one, and now, he would do that as coach, with his charismatic smile and inspiring talks, steely determination, methodical intellect, championship experience, and character.

He seemed to be the perfect hire.

But he wasn’t.

Years later, at the 2004 unveiling of the Bart Starr statue near Lambeau Field, he thanked the fans for their loyalty and said with a humble smile, “even during the coaching years.” The crowd chuckled nervously.

The 1983 season was inconsistent— inexplicable losses and amazing victories. Mid-season, in the highest scoring and one of the most exciting games in Monday Night Football history, the 3-3 Packers defeated 5-1 defending Super Bowl champion Washington, on a field goal with under a minute to play. The dominating offenses—combining for 1,025 total yards (771 by the pass)—zipped up and down the field. The game featured 6 lead changes, 3 ties, 56 first downs, and an impressive 9.1 yards per offensive play by the Packers. At the final horn, the stadium roared as exultant players ran on the field, taking bows, waving to the championship-starved, frenzied crowd. Starr told them to stay on the field as long as the fans kept cheering.

The team was ecstatic, including running back Eddie Lee Ivery, who decided, what the hell, I’ll celebrate all week. “I was so caught up in the excitement, I didn’t worry about consequences,” he said. “If I’m caught, I have enough money for a good lawyer.”

By this point he was addicted to cocaine and alcohol, plus weed, and several nights that week he indulged lustily. The night before the next game, against Minnesota, he stayed up all night using, and was still high when he committed a crucial fumble on the Vikings’ 2-yard line, a turnover that probably cost the Packers the overtime game. And the playoffs. And Starr’s job.

Ivery said, “Without a doubt, absolutely” being high contributed to his fumble.

The following week Starr confronted Ivery about rumors of his cocaine use. Ivery denied it, and Starr said OK we’ll do a drug test—right now. Ivery turned to leave, paused, realized he was caught, turned back, and confessed. For the rest of his life, Ivery praised Starr for his humane approach. “Bart was concerned about me as a person,” he said, “then a player. He treated me like family.” Starr protected Ivery’s privacy by publicly saying he left the team due to “emotional problems.” Starr wrote a statement for Ivery, and Ivery read it to the press.

The honorable Starr said that if he promises confidentiality but doesn’t deliver, “They won’t come to us with their problems.” Unlike many coaches, Starr wanted to know their problems. Starr never divulged how the Packers learned of Ivery’s drug use. When the press finally discovered it, Ivery released a statement thanking Starr for his support and saying he prayed for forgiveness.

The Packers arranged outpatient counseling. Ivery said, “I talked to the counselor high. I lied to him and everyone else. They did drug tests, and I used someone else’s pee, twice.” But he eventually failed a test, and in a meeting with Starr, Ivery lied: “I told him I had it under control, but when I walked out the door, I started crying. I went back in and said, ‘Yes, I have a problem.’”

The Packers paid for 4 weeks of residential treatment at the Hazelden Clinic in Minnesota. “For me,” Ivery said, “Hazelden was 28 days of vacation. I didn’t go to fix my problem. I went to save my job. I didn’t think I had a problem. The Packers still paid me while I was there, so I said, ‘Heck yeah I’ll go.’ I thought, ‘I don’t belong here. I have it under control.” Those losers belonged there, but not him. He enumerated the reasons: “I’m still married. I haven’t lost my cars, pawned belongings, or lost my house. One guy there was paralyzed. Not me.” Ivery convinced a cafeteria worker to bring him weed. “I smoked a joint with her and her boyfriend,” he said. “I went in dirty, and I left dirty.”

But he convinced everyone that Hazelden worked, and that he was drug free. Flying first class back to Green Bay, he ordered a gin and tonic. The team’s top rusher, he missed the rest of the season.

Perhaps one reason Starr was so compassionate is that he knew the agonizing hold that addiction can have on a beloved person. His own younger son, Brett, a few years younger than Ivery, was also addicted to cocaine—the Starr family’s deepest anguish. They—like, eventually, Ivery’s family—experienced years of hopes and disappointments; lies, deceptions, missed family gatherings. Brett would call home, sobbing, apologize, commit to recovery, renew his faith in God, and they would hope, desperately, then he would disappoint them. Repeatedly.

Starr literally treated Ivery like family.

Ivery began using at home in the basement. “I got paranoid about getting caught,” he said, “so I did it down there.” His wife, Anna, wasn’t fooled. “I lied my way out of it,” Ivery said. “I pretended I was down there playing with the dog.” His alcohol consumption was copious. “By then,” he said, “I drank to get drunk. I crossed that ‘imaginary white line.’”

The Packers needed to win the 1983 season’s last game to make the playoffs (which means if they had won the Minnesota game in which Ivery fumbled at the 2, they would already be playoff-bound). But, after leading late, they lost the last game on a field goal with 10 seconds to play. Early the next morning, the Packers president, Judge Robert Parins, tersely fired the legendary Starr. No, “Thank you for 26 years of service…” No, “We’ve come to the difficult decision….” Just, “We’re letting you go.” Afterwards, a shocked and furious Starr closed his office door and wept.

Quarterback Lynn Dickey groused, “He fired him like he was a towel boy. That was horrible.”

Christl said Starr arrived with little experience and “left as a coach who was loved and respected, who remained true to his character, but he didn’t win enough games.” In the NFL, you can be dedicated and compassionate; you can be idolized and deified, but if you don’t win, you’re out.

In 9 years, Starr had only 2 winning seasons and 1 playoff appearance. Only once did they win 4 consecutive games. While Packers fans knew this firing might happen, given Starr’s record, a melancholy pall clouded Green Bay. One fan said, “It was like firing Jesus.”

Packers historian Lee Remmell said, “There was such a feeling of sadness. He was a gentleman, and he tried so hard. He lost sleep, and winning still didn’t happen.”

In his final press conference, a disappointed and emotional Starr quoted Theodore Roosevelt: It’s “not the critic who counts” but “the man in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood….” You can fault me, Starr implied, but I was in the arena, competing. The gentlemanly Starr graciously thanked the Packers for hiring him. He thanked the fans, players, coaches, and staff, from trainers to secretaries. He declared he was still the Packers’ “number one fan” because “no one has more of his heart and soul in this organization.”

He concluded by saying there was some good he had done that perhaps atoned for the disappointing results, and the example he gave was his relationship with Eddie Lee Ivery. He said he had talked with Ivery about a “particular situation” and challenged him to become the player he had the capacity to be. Ivery said he wasn’t sure he could do that without Starr but promised he would. Starr said to the press, “Maybe some of those things make it worthwhile.”

For Starr, his humane way of dealing with people made up for the lack of victories, and the relationship that came to mind at his farewell news conference, out of all the players that Hall-of-Famer Starr had coached, all his coaching colleagues, all the fans he had treated with kindness, was his with Ivery. The player whose fumble—and absence for the rest of the season as their best rusher—was a key reason the Packers missed the playoffs, which cost Starr his job.

In his farewell to Green Bay as coach, the man whose son was struggling with addiction concluded with a touching moment aching for hope. Starr placed faith in compassionate human connection. Starr said that just a few moments before that news conference, he and Ivery had “exchanged a few tears and embraced.” A despondent Ivery told Starr he had never had a father, and Starr replied, “You have one now.”