I ambled through the cathedral in Uppsala, Sweden, down the middle aisle, then along a side aisle, toward the back, where I would turn right to walk between the main chancel and the rearmost chapel—a recessed semicircle at the eastern end of the cathedral, where the sun rises, which makes it symbolic of Jesus’ Resurrection and of spiritual renewal. Along the way, I admired and shot photos of artwork and stained glass. I took in the massive space’s sacred grandeur.

Making the turn, I almost said, “Excuse me.” I thought I had walked in front of a tourist, a lone woman who seemed to be looking intently at the sunlit ornate chapel.

The space she beheld has the remains of Swedish King Gustav Vasa (1496-1560), founder of the Vasa Dynasty and unifier of Sweden in the 16th century. Three stone effigies—his and on either side of him those of two of his three wives—all lie atop his sarcophagus, which was designed by Flemish artist Willem Boy. Seven frescoes on the curved wall depict scenes from the King’s life. Uppsala Cathedral is also the burial site for other royalty and famous Swedes.

The “tourist” remained motionless for too long than is humanly possible. She is, I learned later, a remarkably lifelike, life-size reproduction of a woman, constructed of polyester, silicone, fabric, glass, human hair, and oils. Her hair partially covered by a blue shawl, she wears black boots, a blue coat with white floral embroidery, and a white skirt.

I looked at it from all sides and took pictures. A sign on the wall identifies, in Swedish then English, the name of the artwork: Maria (Återkomsten); Mary (the Return). The sign includes no commentary like the kind often seen in art museums, which explain the artist’s motivation or context.

In the gift shop, I asked what was the story of the life-like woman. The clerk said the space she gazed upon had previously been dedicated to Mary, the Mother of Jesus, until King Gustav claimed that space for his (eventual) tomb. I said, “I guess if you’re king, you can do what you want.” The clerk replied, “Or if you have enough money.”

The cathedral’s (former) Chapel of the Virgin Mary was dedicated to Jesus’ mother in the Middle Ages, but in 1550 King Gustaf declared that’s where he wanted to be buried. Ten years later, he died. Mary’s depictions and tributes were evicted, and the king’s tomb and tributes replaced them. After that, her presence in the church was minimal.

In the early 2000s the Cathedral announced a competition for art that would be a “visible reinstatement of the Virgin Mary inside the church.” The winning proposal, submitted by Swedish painter and sculptor Anders Widoff, was installed in 2005.

Widoff’s Mary, which took him over six months to create, is not depicted as she often is in cathedrals: mother of Jesus, wife of Joseph, or surrounded by virginal, holy glow.

She stands alone, on the floor, not in an elevated position, as are paintings one has to look upward to see. There are no ropes or rails to keep tourists at bay, which makes the piece vulnerable to touch, which, over time, could degrade it. There are no candles or benches, as with artwork that invites meditation and reflection. She stands there, looking.

In an interview, Widoff said, “This is a woman who is quite small actually. She is forty, maybe forty-five years old and stands and looks over at [King Gustaf’s chapel], at the light over there. She is wearing an inconspicuous coat with a slightly oriental cut. I want her to look like you and me, kind of like if she were on her way to the store to buy bread.” He also said, “I wanted to see Mary as herself, as a woman first and not just in covenant with Jesus….” And: “[It] has been important to give her an independent role. She had a pretty troublesome son. It’s a way to give her redress and not just see her as a supporting character.” And: “I didn’t want to make her too beautiful, then it will be a distance.”

Liberation theologians point out something that should be obvious but wasn’t to me until I read their writings: That we all see things from our own perspective, which shapes and influences how we interpret and describe things. It’s a basic aspect of human nature, but before reading liberation theology, I didn’t think of myself as someone with familial, cultural, racial, and gender contexts that significantly (though not completely) shape who I am. These theologians are sometimes faulted for having a limited perspective, but one of their assumptions is that ALL of us have a limited perspective.

Here are some comments I found in an online search for others who interpreted “Mary (the Return)”:

“a strange, small woman”

“her shy gaze”

“That Jesus’ mother has been placed in such a hidden place, so inconspicuous, feels as if she is being devalued, as if she has been placed in the corner of shame.”

“…composed, and seemingly deep in prayer. I took her for a refugee.”

“unassuming woman, quietly dignified and resolute, gazing unflinchingly towards the East window.”

“Maria’s careworn look is emblematic of the suffering and courage of so many women around the world.”

What makes her “strange” or “shy” or “resolute” or “careworn” or a “refugee”? Of course her gaze is “unflinching;” she’s a sculpture that can’t move.

When I learned the backstory of this Mary, I recalled a movie I saw (I can’t recall the title. Help anyone?) in which a family was forcefully displaced from their home by aggressive forces, and they fled to another country. Years later, the father of the family returned to their home to find it occupied by a friendly young mother with a child. He visited her cordially and looked at rooms and spaces that evoked his family memories, without telling her it was his former home wrongly taken. The scene was powerful even without outrage that he could have righteously expressed.

My thoughts that I projected onto Mary: She looks wistfully at her former “home” from which she was ousted by a powerful monarch. (Not even the mother of Jesus could stop that.) She used to belong there; now she doesn’t. But being drawn “home” is a strong human impulse.

I haven’t lived in Clinton, Mississippi for 45 years, having left after I graduated college in 1980. But I grew up there, and it still feels like home. My childhood and adolescence were steeped in the state’s culture, traditions, and many contradictions. In contrast with Mary’s former cathedral nook and the home of the returning refugee in the movie, the house in Clinton I return to is still occupied by my family, and when it no longer is, it will be because we sold it willingly—not because it was taken away.

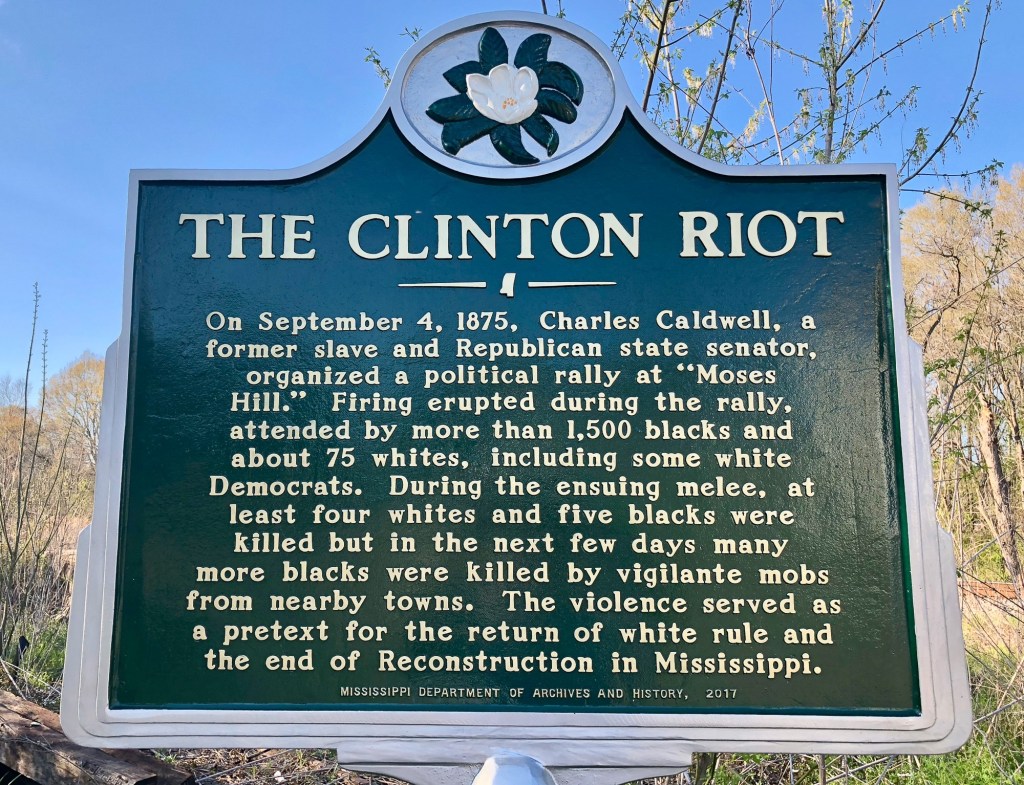

In the aftermath of the Clinton 1875 massacre, in which 50 Black and 3 White citizens were killed over 4 days, many Black Clintonians fled their homes and never returned. One of my ancestors, alas, led a contingent of the White marauders. “Home” is different for different people with different stories.

Welcome back, Mary. May the memories be sufficient.