In Stockholm, between Nationalmuseum (the Swedish national gallery of fine arts) and the Nybroviken Bay waterfront, where tourists board and exit ferries and sightseeing boats, or sip a beer while enjoying the view, rises a gleaming stainless steel 40-foot tall arch.

Created by Chinese artist and human rights activist Ai Weiwei, the artwork, entitled simply “Arch,” resembles a cage with a curved top, its inner walkway shaped like a silhouette of two people embracing.

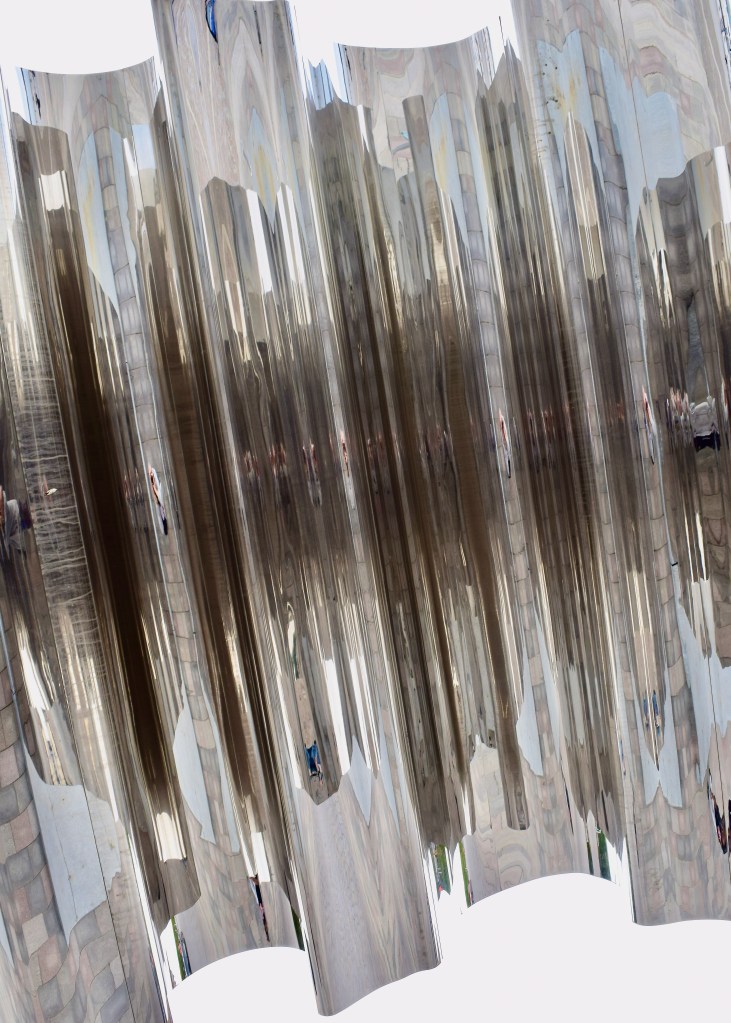

Many passersby stroll through that opening, amused by their images distorted by the curved, polished, shiny interior, reminiscent of fun-house mirrors that make us comically thin or wide, or weirdly misshape our heads. Children laugh, pointing at their goofy face—or Mom’s or Dad’s.

So it’s fun, but it also can be seen as two people ruining the purpose of a cage: trap people inside; keep outsiders out. The silhouetted figures didn’t merely escape the cage; they broke all the way through it. The shiny surfaces inspire literal and thoughtful reflection. One commentator referred to the “vulnerable gentleness in the curves of the cut-out figures.” They went on, “The figures that hold each other at the centre of the sculpture, cut out of the bars, remind us of the basic values of equality, trust, empathy, and social responsibility for our fellow human beings.” An embrace is basic humanity, strength in the midst of struggle. Sometimes, it takes an accomplice to accomplish something.

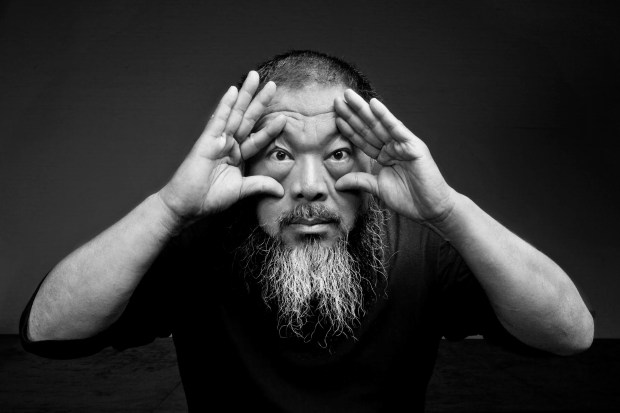

Ai Weiwei, whose conceptual art can be bitingly—but often not overtly—subversive, is internationally praised but has been treated harshly by the Chinese government for criticizing their deficiencies regarding democracy and human rights. In 2011 he was arrested and held for 81 days without charge, generating international protest, then not allowed to leave the country for four years. He has since lived in Germany, England, and Portugal.

After the 8.0-magnitude earthquake in Sichuan province in 2008, Ai led an effort to memorialize the names of over 5,000 children who perished in poorly constructed schools that collapsed, while many nearby buildings remained standing. For the 2013 Venice Biennale, Ai created an installation, entitled “Straight,” composed of 150 tons of twisted, contorted steel rebar clandestinely salvaged from the rubble of schools destroyed by that earthquake. Ai’s team hand-straightened each metal bar.

We happened to be in Venice that summer. The emotional power of the installation is hard to convey, unless you saw it. At first, it looked like a pile of discarded construction metal, but, after reading on an explanatory sign the source of the metal and that Ai was commemorating the lost children, we noticed the bars were arranged to evoke the undulating movement of ocean waves, or perhaps flags waving in the wind. (One of the few structures that remained upright at one of the earthquake-damaged sites was a flagpole topped by a windblown flag.) Waves can be soothing, flags patriotic, and this art turned those thoughts upside down. The mangled-then-straightened steel—visually, metaphorically—holds to account governmental corruption and neglect.

Such is the power of Ai’s art. He can evoke emotion and deep contemplation on the world around us. He creates work that defies the barriers of language. Both “Arch” and “Straight” combine art and activism.

According to Ai, “Arch” was originally about racism and the global refugee crisis caused by regional insecurity. Interpretations changed over the years as issues emerged, such as the U.S. immigration crackdown and the isolation created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Ai said in an interview, “Our world is more uncertain and unstable than any other time during the previous half a century. Against such a backdrop this work is once again a warning and reminder.” He said, “It’s more relevant to us as we all face the challenge of walking out of the cage of our thoughts, life conditions, and wars, to enter the state of peace and health.”

Ai said “Arch” calls for the free passage of all populations, and a world without borders. Like John Lennon’s “Imagine,” (“Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for… You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will be as one.”) it is idealistic and unrealistic, but provocative. “Arch” evokes visions of our shared striving for human connection, freedom, and peace.

“Art should be something that liberates your soul, provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further.” – Keith Haring, New York City graffiti artist