The cathedral in Freiburg, western Germany, much like the Packers’ Lambeau Field in Green Bay, Wisconsin, looms vastly out of proportion to the city around it. Both cities have modest populations but enormous edifices that dwarf surrounding buildings and attract gawking tourists from around the world. Both have statues of revered figures. You can pay to tour them both. One is overtly religious; one may as well be.

Construction on the Freiburg cathedral started around 1200 in the late-Romanesque style (towering round arches, massive stone and brickwork, small windows, thick walls) and was later finished in the Gothic style (pointed arches, stained-glass windows, flying buttresses, ribbed vaults, and spires). Its construction took over 300 years, so most builders and designers never saw the finished structure.

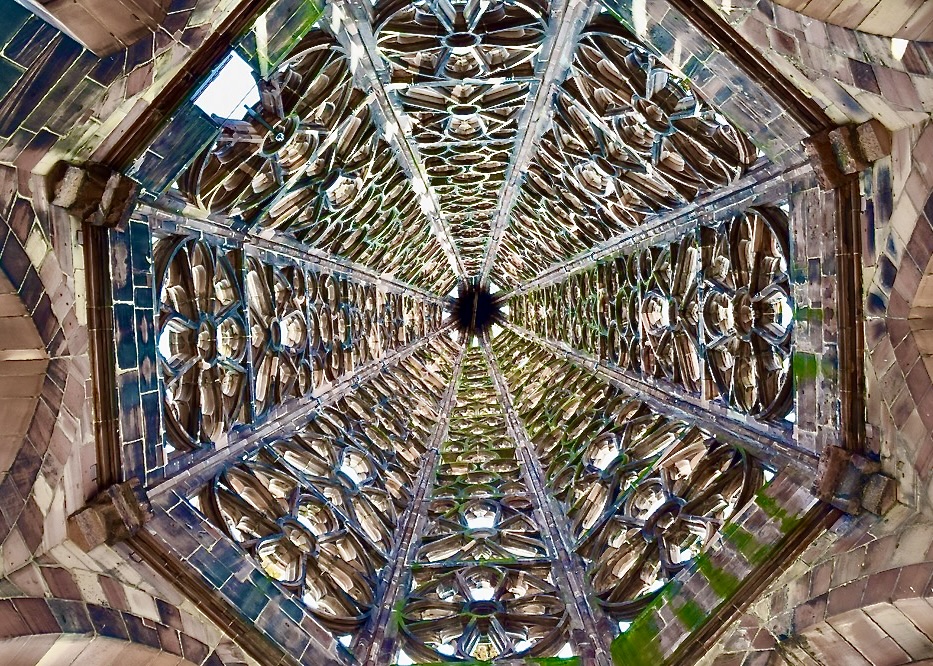

Its most prominent feature is the 380-foot tall ornate spire, the first spire in the history of Gothic architecture built with open lattice. Bottom to the highest viewing platform open to tourists is 335 steps.

Among the cathedral’s 19 bells, 16 of them in the tower, the oldest and most famous is the 750-year-old, 3-ton “Hosanna bell,” one of Germany’s oldest Angelus bells, which are rung before the traditional Catholic Angelus prayer service (a celebration of the Incarnation of Jesus) and each year on 27 November in remembrance of fierce Allied bombing raids in 1944. The Hosanna’s ring is said to be “unmistakable: melancholic, loud, and clear.”

The cathedral survived the air raids, which left nearly all of the old part of the city around it in rubble. The tower vibrated violently but held firm due to the secure lead anchors firmly binding its sections. The windows had been removed from the spire prior to the bombing and also suffered no damage. It is built to last.

The cathedral has one of the world’s largest “Lenten veils” (also known as “fasting cloth”), at 10×12 meters. It was created in 1612 and features a large painted Crucifixion scene. The largest in Europe, it has been displayed for the last 400 years from Ash Wednesday until Holy Wednesday (which commemorates the Bargain of Judas as the betrayer of Jesus—also called Spy Wednesday). It was customary in Europe during the Middle Ages for the veil to completely separate the main altar (chancel) from the rest of the church. Some say that placement was for the congregation to focus on listening as they could not see the liturgy being performed—a form of “visual penance”—to remind Christians of their sinfulness and to encourage repentance. See no liturgy, sense your guilt. Nowadays, Lenten veils are utilized in some parts of Austria and Germany, more to indicate the beginning of Lent and less to block the view of the chancel. In 2003, the Freiburg Lenten cloth was repaired and given a supportive backing and now weighs over a ton. Moving it requires special machinery.

The cathedral’s high altar features a multi-panel painting by prominent German Renaissance artist Hans Baldung, who created altarpieces for many cathedrals. (He was also infamous for painting scary witches in forests casting evil spells, which contributed to witch hunts in the 16th and 17th centuries.) The altarpiece and the cathedral itself are dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

External masonry features, such as gargoyles (there are 91), are damaged by weathering and pollution, so the cathedral is a continuous repair site. One gargoyle bows toward the building and points its rear end at the city council building, and, according to a legend, was created by a disgruntled stonemason who was not paid the amount he expected by the council, which is forever saluted rudely. There is a spout for water to pour downward where you-know-what would be excreted from that part of an actual person. Next to it is one with its head leaned forward, buried in a book, a drainpipe emerging from the top of its head. Gargoyles direct water away from the building and were thought to ward off evil spirits—which, according to the city’s website, “is why many of these eerie creatures are depicted with tortured, screaming mouths.” (One theory is that the mooning gargoyle keeps the devil at bay with its outward facing posterior.)

According to an economic analysis of cathedral building, in the years 700-1500, such construction was “the expression of many impulses: religious, economic, political, artistic and cultural…. They required enterprise, planning and organization of a high order, substantial inputs of capital and labour (skilled and unskilled), and assemblage of impressive quantities of resources – stone, brick, lime and sand, timber, iron, lead, copper, glass and much else…. Prosperity and confidence in the future were good for church building.” Economic good times featured robust cathedral construction, and technological advancement brought new features, plus more jobs and income.

Even in the religious realm, size matters. A cathedral, the bishop’s home church, is often a town’s most imposing building and one of its most ancient. It’s the central church of a diocese, indicative of the bishop’s high status in the hierarchy and is larger than parish churches led by mere priests. The large, prominent bishop’s chair is situated above both laity and other clergy.

Cathedrals are there for God’s (and the bishop’s) glory but are woven into the secular community around it. Cathedrals attract tourist eyeballs (like mine) and money. In the bustling courtyard surrounding the Freiburg cathedral, vendors sell art, crafts, souvenirs, and clothing. Restaurants serve diners on nearby streets. Cathedrals have served as sites for the staging of non-religious events, such as coronations, and as tombs for princes. Some display trophies celebrating state power, like the griffin atop the east gable of the cathedral of Pisa, a large gilded bronze statue of the mythical beast created to memorialize naval victories in the Western Mediterranean.

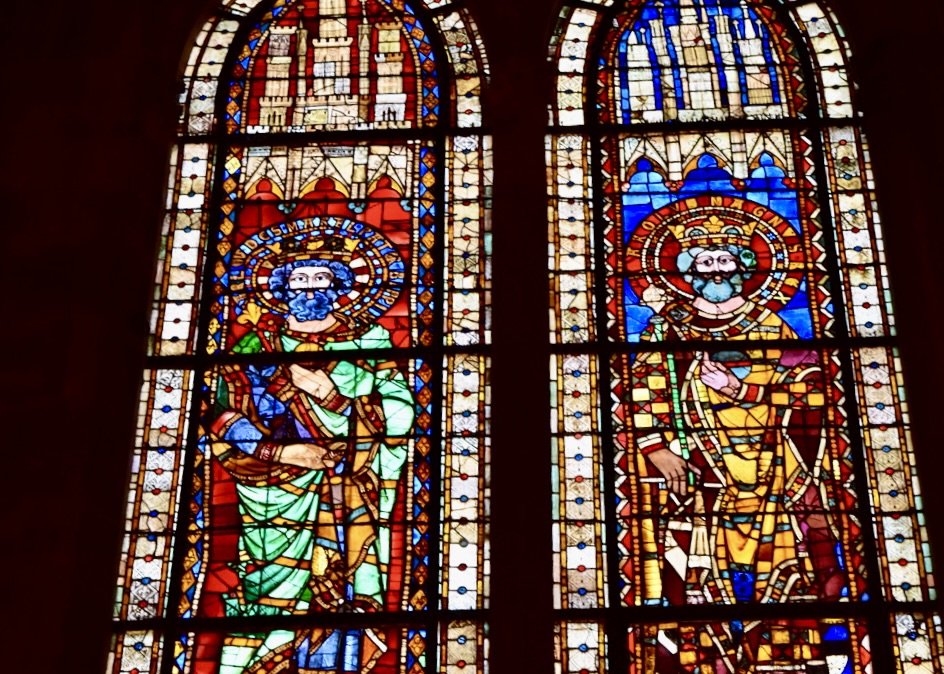

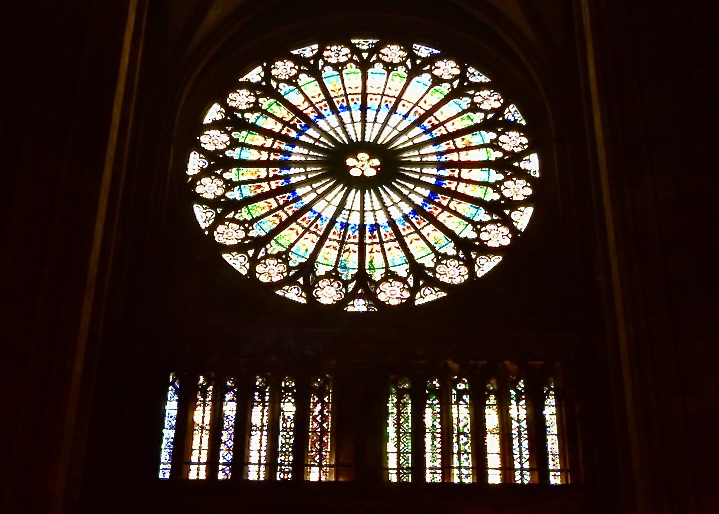

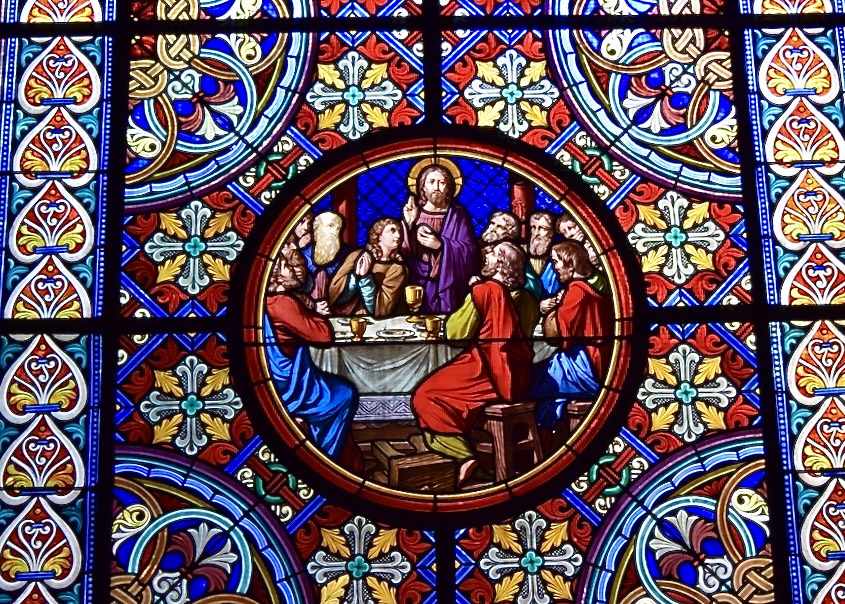

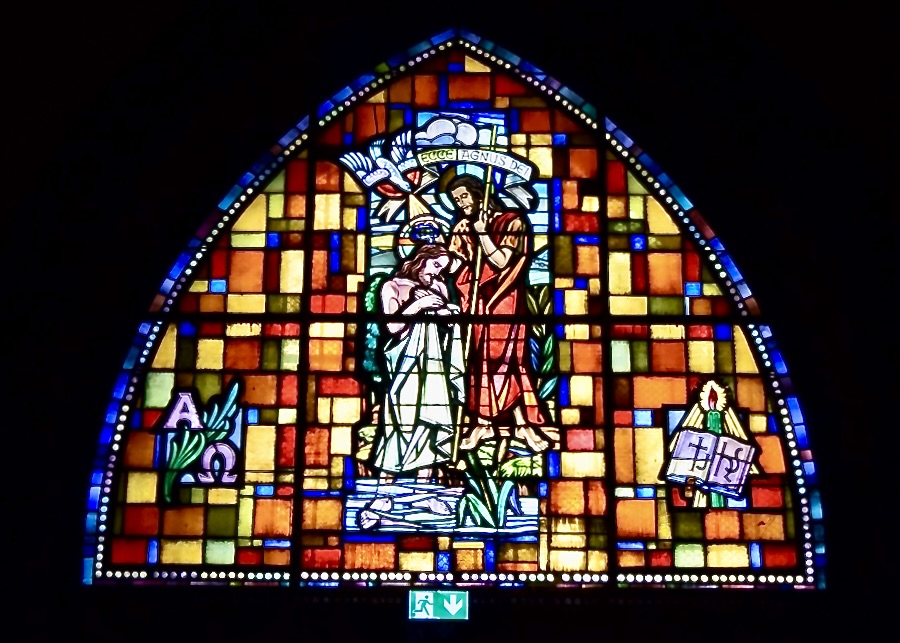

I felt appropriately awed by European cathedrals, their spacious interiors and massive building materials. How, without modern equipment, did they elevate impossibly heavy stones and bells so high? Meticulously crafted and brilliantly colored stained glass windows glimmered. I admired artwork by famous painters, as if in a museum. Cathedrals felt like special spaces: human ingenuity, wealth, and strength commandeered to foster awe of the divine.

Yet I also felt like an outsider. While I have stretched beyond my Christian origins to appreciate beliefs and practices different from mine and while I felt the sacredness of each cathedral, the Mississippi Baptist inside me lurked. In my formative years, church buildings were almost irrelevant. We wanted them to keep the rain off, look nice, and function well (I really wished my church had a gymnasium), but a painting by an accomplished artist would have been a distraction from focusing on Jesus. That kind of money could send missionaries to spread the Gospel in a far-off land. Our stained glass windows were mass produced, plain, with no interesting designs, ordinary collages of colors. We valued solid construction, comfortable pews, and reliable air conditioning (think Mississippi in July). The building was valued mainly according to whether it allowed heartfelt worship to happen inside it.

A gargoyle? That would have been too close to a pagan idol. Psalm 115 says idols are useless and deceptive, and #1 of the Ten Commandment warns against creating a “carved image” and tersely declares God is “a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me.” Who wants to risk jealousy-driven iniquity on their grandchildren and great-grandchildren?

Of course, we Baptists have our own style of hierarchy and ways of exerting power (often while feigning humility), but my church didn’t enshrine status in the architecture. The pastor (my father) didn’t even have a reserved parking spot, much less his own perch above the congregation.

What counted for us was this: Was Jesus your Lord and Savior? Had you genuinely—not because everyone else in your town did or because your parents hoped you would—invited Jesus into your heart? You could do that anywhere, in any structure, religious or not, or while swimming in a pond. If you hadn’t, you were bound for eternal torture in hell and your life had no meaning (even if you thought it did).

I grew up prejudiced against formal, liturgical worship styles commonly used in cathedrals—with their pre-written prayers and historical statements of faith. To us, prayers had to be spontaneous or they weren’t genuine. In my provincial mind, “liturgy,” with its whiff of rote recitation, was alien to inspirational worship. Only later did I appreciate how liturgy can express holiness and reverence, can remind us of the mystery of faith, that there are things we can’t explain, yet we live faithfully anyway.

I visited the cathedrals more for historical and artistic reasons than religious. I can’t say I felt very spiritual in them.

Until something happened at the fabulous Strasbourg cathedral, the Cathédrale Notre-Dame-de-Strasbourg.

For 227 years, it was said to be the tallest building in the world and is now the world’s sixth tallest church. Hundreds of exquisite sculptured figures with fine detail cover the front façade, depicting scores of biblical scenes and other significant religious events, such as the martyrdom of Saint Laurent (allegedly, for insulting a prefect). The color of the exterior’s reddish-pink sandstone changes according to the time of day and the color of the sky. Like that of Freiburg, its towering spire is elegant and intricate. Its Renaissance astronomical clock (its mechanism dates from 1842) features a parade by the apostles every day at half past noon. The place is a marvel.

I wandered the interior taking pictures and admiring. I watched—and photographed—people lighting candles. The usual splendid features—altars, paintings, sculptures, architectural designs—impressed, as intended. I barely noticed the actual worship service at the front, until I ambled closer. The front pews were packed with young adults, which seemed unusual. There was a palpable energy I didn’t associate with a staid, ornate cathedral. When the service ended, a security guard efficiently—and firmly—escorted everyone away from the front.

My German friend Andrea and I walked outside where we were surrounded by the crowd of young adults who had been at the front of the cathedral and had exited around us. They spontaneously began singing songs of praise. Andrea, who speaks French, asked someone about the gathering, and she was told it was the culmination of a multi-day pilgrimage. They had walked from town to town, ending in Strasbourg, along the way attending spiritual meetings to deepen their faith, to experience, as they told Andrea, “the joy of the Lord.”

Joyful indeed, they smiled and hugged, celebrating the journey’s end. The singing was full and exuberant, their ebullient mood infectious. There was no energetic or frenetic shouting that I associated with Protestant charismatic worship. It was a measured exuberance. This time, being present at a cathedral—an ancient structure that I mostly associated with secular history and practices foreign to my Baptist roots—stirred my spirit. Next to the old gigantic stones, my heart was warmed. I cried tears of fond memory. The fervent faith of youth can be naively hopeful and sunny (pray and the world will bend to your prayers), but it also can be inspiring. The Spirit punctured through my assumptions and experiences, and touched me.

I found this article very well researched and a delightful read. A very nice job again done by Jerry Gentry.